Author: Alex MacKenzie, Local Food Development Manager, Tagsa Uibhist

Report funded by Nourish Scotland and the Scottish Government – Fair Food Transformation Fund

August 2023

Uist & Barra

Tagsa Uibhist, in partnership with Nourish Scotland, conducted a study in 2023 to look at the affordability and accessibility of basic fruit and vegetable items in Uist and Barra and to compare these findings with mainland data. This study built on Nourish Scotland’s research into understanding what the right to food looks like for families living in Scotland and explored what people in Scotland would choose as a healthy and enjoyable way to eat if incomes and benefits were sufficient.

In 2021, Nourish Scotland worked with groups of community advisors to co-create weekly shopping lists that considered the realities of people’s lives and preferences, while aiming for a ‘good enough’ fit with current dietary recommendations. These shopping lists formed the basis of our research in Uist and Barra and act as tools for measuring progress locally and nationally. Nourish Scotland worked with partners across Scotland, including Tagsa Uibhist, to investigate, compare and make sense of how the availability and price of these foods differ within and between local authority areas.

Owing to the much documented difficulties with island supply chains, Tagsa Uibhist felt it was prudent to gather local data to highlight the challenges and effects of food insecurity on the Western Isles population. The research findings evidenced that people living in Uist and Barra are disproportionately more disadvantaged in terms of affording and gaining access to basic fruit and vegetable items. Less than half of the shopping list items were easily accessible and furthermore the total basket cost was 28% more expensive than a Tesco Online shop. These findings were in stark contrast to other rural mainland communities and evidenced worrying trends on the dietary inequalities for island communities. Communities who rely heavily on long food supply chains challenged by ferry problems and the rising cost of fuel, agricultural inputs, food and living costs.

There is a strong call, by our community researchers, for immediate and progressive action by national and regional authorities to address these difficulties in a meaningful way. Action which promotes a truly dignified island food system; one where everyone is food secure, with access to adequate, nutritious, and culturally appropriate food, without the need of emergency food aid. It is one where the right to food is understood as a matter of justice rather than charity and allows for a Good Food Nation in which every community’s health and well-being is paramount and no-one is left behind. Our island communities demand nothing less because, of course, a right to food is a right for all.

There is a strong call by our community researchers for immediate and progressive action by national and regional authorities to address the difficulties of food insecurity in Uist and Barra. Food supply chains are fundamentally broken, and our findings show that the health of islanders is compromised by limited access to adequate, nutritious, and affordable food particularly during the winter months. Our community researchers recommend the following:

We are delighted to release our new report – ‘Our Right to Food – Uist & Barra'. Our right to food survey was a community endeavour, led by our community researchers, to explore, compare and make sense of how the availability and price of foods differ across the islands and against mainland prices and supplies.

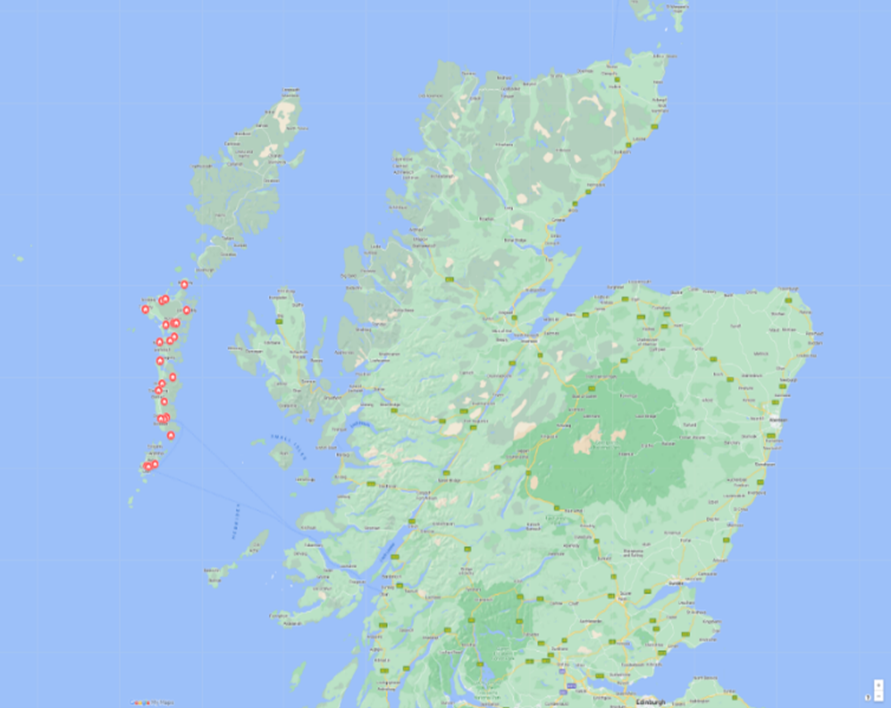

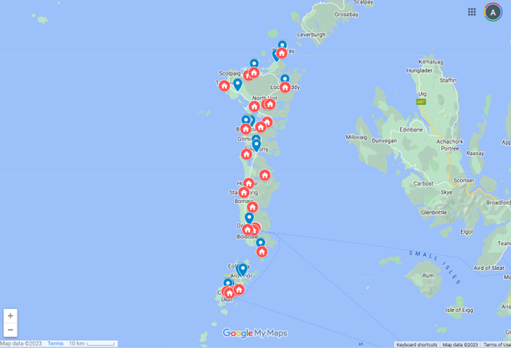

A special thank you goes to the 24 community researchers from Berneray to Barra (see below), representing 8 Outer Hebridean Islands, who took on the Anneka Rice challenge of surveying all the shops in Uist and Barra over a two-month period. We also want to thank our partner organisation, Nourish Scotland, in particular to Irina Martin, Pete Ritchie and Chelsea Marshall who supported us on this journey to give light to the challenges of food insecurity in Uist and Barra. We are also grateful to all the participating local shops, supermarkets, market gardens and mobile vegetable van who provide a vital service to the community in a challenging environment.

In Scotland we have adopted a human rights approach to tackling poverty and food insecurity, founded on principles of dignity and respect. The Scottish Government is committed to tackling inequalities and building a fairer, more equal Scotland where people from every walk of life take pride and pleasure in, and benefit from, the food they produce, buy, cook, serve, and eat each day. Scotland's Good Food Nation policy provides the high level ambition and cross-government coordination to ensure people have access to affordable, locally produced and nutritious food. A human rights framework can enhance our vision for a Good Food Nation and is an important step towards improving social, economic and health outcomes and a key marker of progress towards realising the right to food. Scotland, as part of the UK, is signed up to international human rights laws protecting the right to food however, the right to food is not currently incorporated into Scotland's domestic laws. Scottish Government has the opportunity in their new Human Rights Bill to show leadership in a practical way by incorporating the right to food into Scots laws as part of its work to make Scotland a Good Food Nation.

Yet, for the right to food to be realised, food must be adequate, available, and accessible to all. Sadly, it is widely recognised that too many people in Scotland cannot afford the food that they need to keep them healthy and well, and that the financial pressures on some households are greater than others. Furthermore, the Scottish diet has stayed fixed for years – making little progress towards meeting the government’s dietary goals – and people living in the most deprived areas remain more likely to experience diet related ill health.

We also know that in rural, remote and island areas the cost of living is substantially higher than in towns and cities partly because of distance to services and large shopping centres offering lower prices. Fuel poverty is also more prevalent in rural areas. In the Scottish islands living costs are even higher than in rural mainland areas, particularly in relation to island delivery costs and there are frustrations about the cost of food, lack of choice and access to budget supermarkets. It is recognised too that the elderly, of which in the Western Isles has a high proportion living on their own, are more likely to face higher food costs as they would be more regular customers at local, more expensive shops than the larger supermarkets.

In order to address the gap between the challenges we face and our shared vision of a Good Food Nation, we need to fully understand what the right to food looks like in today’s Scotland, measure how financially and geographically accessible this is for people in different situations and begin to ask how government policies are helping to progressively realise the right to food.

Our right to food can mean different things to different people but a shared vision put forward by Nourish Scotland is - A Scotland where everyone is able to afford food that keeps them healthy and well.

Nourish Scotland advocates that everyone should be able to afford the food that keeps them healthy and well, but this does not mean that food should be cheap. It means wages and benefits should be high enough that people can choose the food that helps everyone in the family live a healthy life, without having to sacrifice other basic needs like heating.

The right to food can be broken down into different elements.

Availability - food should be available for sale in markets and shops. Food should be available from natural resources.

Accessibility - food must be affordable. People should be able to afford food for an adequate diet without compromising on any other basic needs, such as school fees, medicines or rent. Physical accessibility means that food should be accessible to all, including people who are physically vulnerable.

Adequacy - food must satisfy dietary needs. Food should be safe for human consumption and free from contaminants including residues from pesticides, hormones, or veterinary drugs. Adequate food should also be culturally acceptable so religious and cultural taboos must be accommodated.

Food insecurity is a major public health concern, and refers to the uncertainty, lack of, or inability to acquire nutritious food in a safe and socially acceptable manner. Food insecurity has been associated with obesity and unhealthy dietary patterns, both of which can have negative health consequences. The cost-of-living crisis has had a serious impact on the poorest households who spend a much greater share of their budgets on essentials. These essentials – such as food and fuel – are experiencing the greatest rises in cost. UK food price inflation rose to 19.1% in March the fastest annual increase in food and drink prices since 1977 adding to the pressure from sky-high energy bills amid the cost of living crisis. Annual grocery inflation has now dropped to 12.7% in the four weeks to 6 August but while inflation – the rate at which things get more expensive – is expected to fall, prices are not reducing significantly. What we are paying for food now is the new normal. This will have a critical impact on health through limiting individuals’ ability to afford basics and necessities for a healthy standard of living, such as a warm home and enough nutritious food.

Cost is often cited as a barrier to healthy eating, particularly for those on low incomes, as evidenced within Food Standards Scotland (FSS) consumer tracker surveys. With food prices on the rise, driven by both domestic and global factors, this has contributed to changes in shopping habits as the cost of people’s weekly shop has increased. FSS reported in 2022 that healthier foods can be up to three times more expensive than less healthy foods, which make it even more challenging to purchase and consume a healthy diet.

Consumers are doing what they can to offset the impact of inflation, with many switching to the cheapest own label lines. Total spending on these value ranges has rocketed by 41% compared to last year and retailers have been quick to respond, expanding their offerings to meet demand. A Joseph Rowntree Foundation survey in 2022 highlighted that families in Scotland have changed how they shop, prepare and how often they eat food. One in three households have reduced the amount of money they spend on food for adults and one in five have skipped or reduced the size of their meals. For low-income households the impact is starker with one in five households on low incomes in Scotland going hungry and cold as a result of the cost of living crisis with nearly four million children across the UK experienced food poverty in January this year.

Small island communities who rely so heavily on long food supply chains are especially vulnerable; the rising cost of food is being felt by households in the Western Isles and is exacerbated by ferry problems and the rising cost of fuel. Evidence shows that the cost of living in remote and rural Scotland including the islands is between 15% and 30% higher than urban parts of the UK. The cost of remoteness is making it more expensive to meet a minimum acceptable living standard for these rural areas of Scotland. A ‘rural premium’ is widely documented where essentials cost more the further the distance from urban areas and is often exacerbated by a poverty premium in which people in poorer rural areas are paying more for their essentials than those in the less disadvantaged parts. In addition, paying for food can cost more in remote areas as a result of higher retail prices at different kinds of store but for families with children and single pensioners on islands this can be an additional 10% or more increase to food budgets. The disparity can be even greater on certain islands not serviced by larger or budget supermarkets. In the 2014-2017 Scottish Health Survey for each NHS Board and Local Authority area obesity rates were significantly higher in Na h-Eileanan Siar (34%) compared to the Scottish average (29%). . Highlighting it can be more difficult to eat healthily when healthy food choices are more expensive and less available.

Shoppers across the UK continue to find ways to offset the impact of inflation on their household budgets by switching to supermarkets’ own-label products or shopping in budget supermarkets. The hunt for better deals has boosted the discounters Aldi and Lidl who continue to take a bigger share of spending from their rivals, recording the fastest pace of growth in the market. Whilst everyone across the country has been tightening their belts to cope with the cost of living, people in rural areas don’t have the same access to lower cost food which includes access to food banks. This, in turn, leads to a reduction in the real purchasing power of rural consumers and creates “food deserts” as an area poorly served by food shops where people without adequate transport or limited mobility struggle to access healthy food.

Tagsa Uibhist during October 2022 – March 2023 worked alongside Nourish Scotland to look at the affordability and accessibility of basic fruit and vegetable items in Uist and Barra. We recruited 24 community researchers from Berneray to Barra, representing 8 Outer Hebridean Islands, to undertake this study. Our right to food survey was a community endeavour, led by our community researchers, to explore, compare and make sense of how the availability and price of foods differ across the islands and against mainland prices and supplies.

Our community researchers set out to find a mixture of fruits and vegetables from an example weekly shopping list for a family of five. The list was developed by a group of community advisors, with input from public health nutritionists, who had worked together to identify a balance of foods that would fit the needs and aspirations of a large family living in Scotland today (the ‘Robinson Family’). Our study is based on a family profile of two adults and three children (aged 7, 10 and 15) and was chosen as this household type along with households with single adults with two young children are at higher risk of food insecurity in Scotland.

Our shopping list is comprised of 17 basic fruit and vegetable items including fresh produce, frozen goods and pantry items and provides the basis for a ‘right to food’ metric in terms of the affordability of a healthy diet.

After looking for the items and recording their results, community researchers came together online to reflect on what they had learned and discuss what could be done to overcome barriers to accessing healthy foods in their community.

In January and February 2023, 24 volunteer community researchers from across Uist and Barra set out to explore the availability and price of a variety of fruit and vegetables in their own communities. The research focused on the 17 fruit and vegetable items that community advisors agreed a large family – the ‘Robinson Family’ – would need for their breakfasts, lunches, dinners, and snacks.

Volunteers looked for these items in their local area and completed either an online or paper survey to record the items and prices that they found. They also recorded their views on what the Robinsons would do if an item was not available.

Figure 1: The Robinson Family’s weekly fruit and vegetable shopping list

All of the shopping outlets between Berneray and Barra were surveyed, which included small or large supermarkets, convenience stores, independent shops, market gardens and a mobile fruit and vegetable van. In total, 63 surveys were completed, and a number of workshops were held with our community researchers to sense check the data. This also allowed the opportunity to gather further analytical evidence to complement the quantitative data.

The findings from this study were released at a Dignity Dialogue event on the 17th March attended by Peter Faassen de Heer, Senior Policy Manager from the Scottish Government Directorate for Population Health; Jason Little, Policy Officer from the Scottish Government Tackling Food Insecurity Team; Domhnall Macdonald, Economic Development Manager at Comhairle nan Eilean Siar (Western Isles Council); Pete Ritchie, Executive Director at Nourish Scotland; Irina Martin, Dignity in Practice Programme Officer for Nourish Scotland; Council Leader Paul Steele, local councillors, community researchers, independent shops representatives, Co-op pioneer volunteers and third sector representatives. One key outcome has been the setting up of a local food lobbying group to tackle key issues and on the recommendations of Peter Faassen de Heer from Scottish Government we hope to submit our findings to MSP Jenni Minto – Minister for Public Health.

Figure 2: Location of community researchers

January through to March are described as ‘hungry months’ for the islands, as local produce is not in season and there is a greater reliance on mainland goods delivered by ferry. Ferry services are often cancelled or delayed because of bad winter weather; but with disruptions in the Calmac lifeline services due to an ageing fleet predisposed to breakdowns this compounds the problems further. Frequent ferry disruption means that shelves are often empty in shops, particularly fresh fruit and vegetables. Climatic variations exposing the Outer Hebrides to more frequent storm events and delays in new Calmac vessels regularly leave the islands with no food deliveries, the worst example being up to 5 consecutive days of no supplies this year.

The impact as described by one Co-op manager is considerable because of the centralised automated ordering system that is in place for all the Co-op stores. A just-in-time inventory management system in which goods are received only as needed and are dictated by store sales. However, this doesn’t work in an island context with ferry delays as a result of weather, technical or timetabling issues. For example, delivery vehicles can be waiting at the Uig port in Skye to get across in refrigerated wagons, but the perishable goods are on the clock and will soon go out of date. Co-op delivery vehicles can’t be re-routed to other stores and if there are several delays in the service there will be a backlog of vehicles at port, resulting in all the food stock needing to be date checked and scanned for wastage by the island store. Furthermore, if people start panic buying due to ferry delays, the system will send that same volume of goods the following week creating gluts and wastage on some product lines. Conversely, if there are no deliveries and in-store takings are down the system will adjust to this new level of buying behaviour and send a more limited volume of stock for the following week. The Creagorry Co-op manager claimed that the last 12 months have been the worst they have experienced in all the time they have worked on the islands.

In addition, there were very few smoothie options (a fruit substitute particularly for children) anywhere on the islands and what was there was very expensive.

“Even using fresh fruit to make your own [smoothie] was prohibitively expensive.”

On further investigation it was revealed that two out of the four Co-operative supermarkets between Berneray and Barra are classed as convenience stores. The classification of a Co-op store is dictated by the footprint of the store and the revenue the store generates. There are three classifications: convenience, local supermarket and super store. In a convenience store much of the shelf space is given over to convenience food such as ice cream, crisps, fizzy juice, and pizza. There is also a more limited range of Co-op’s own brand or value range produce within a convenience store as preference is given to top brand goods (Coca-Cola, Kellogg’s, Heinz, Hellmann’s). Yet there is a move towards stocking more branded goods in all the Co-op stores in Uist and Barra which are more expensive than Co-op’s own brand produce.

In terms of availability of produce, the independent stores fared better because they have autonomy over their ordering, can stock local produce and in some cases have access to the full Co-op catalogue. Co-op stores need agreement from headquarters to stock local produce and one of the requirements is that the producer caters to all the Scottish Cop-operative supermarkets which deters small scale local producers.

Though outwith the scope of this report as it refers to meat products, another worrying trend noted by our community researchers is the display of meat products in security boxes in some of the Co-op stores. This method of displaying produce runs contrary to the end of the road honesty box schemes which are prevalent throughout the islands and opened up the question of how islanders access food in a dignified manner through the main shopping outlets. This is not a distinct practice for island stores as the Co-op uses security tags for their higher value products which are prone to theft in all their Scottish stores and as one Co-op manager commented ‘unfortunately it is a sign of the times’.

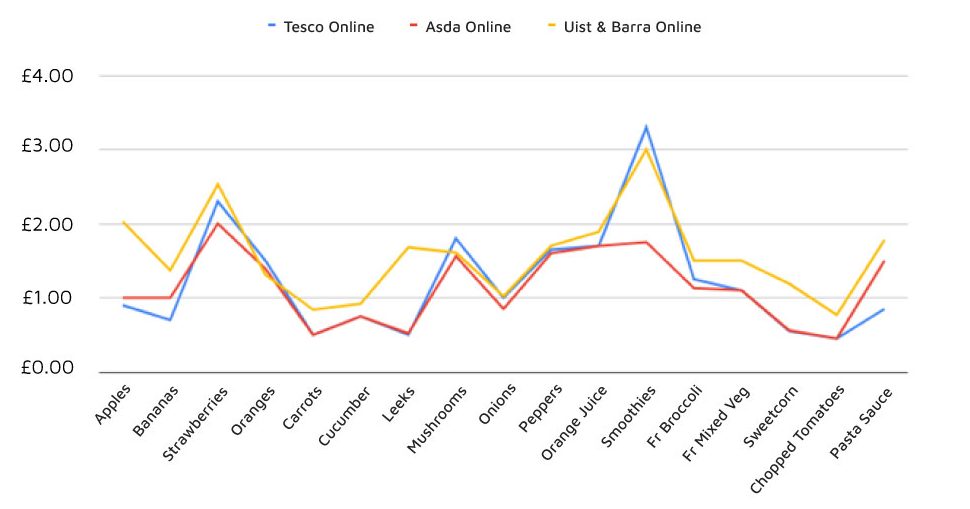

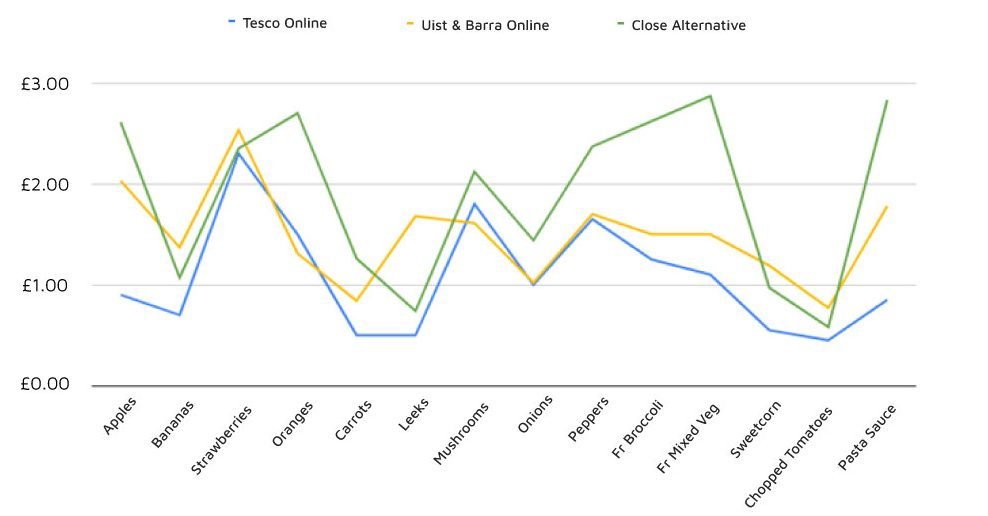

The research confirmed our concerns that an ‘island premium’ exists for people living in Uist and Barra who need to pay close to 30% more for their basic fruit and vegetable items compared to a Tesco online shop.

The total basket cost to buy all the 17 fruit and vegetables items in Uist and Barra is £26.64 which compared with £20.80 for a Tesco online shop; equating to a £6 difference. The cumulative effect of buying this basic composite of fruit and vegetable items week on week, month on month, will be significant for island households. The average price dropped to £19.36 when we included an Asda online shop which only Barra residents can avail themselves of because Barratlantic are the main delivery vehicle for Asda online orders. However, these figures did not consider delivery charges and transport costs for picking up this order at the Barratlantic base at Ardveenish.

Figure 3 – Total basket costs against mainland prices – Uist & Barra shop against Tesco Online = £5.84 / 28% price difference

(Please note recorded prices relate to supermarket figures from Jan – Feb 2023 & may have fluctuated from our survey period)

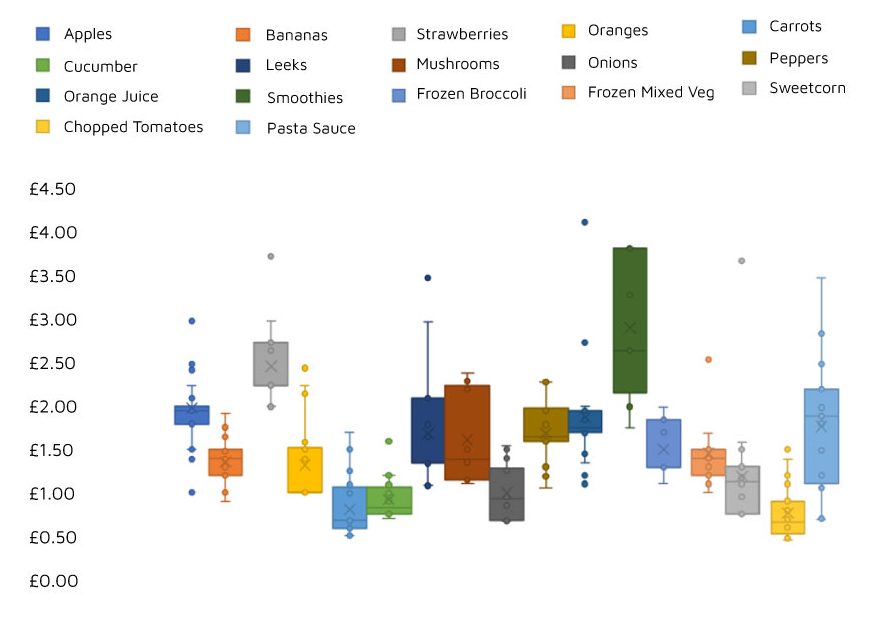

The biggest price variation was shown in apples, bananas, carrots, leeks, frozen mixed vegetables, and pantry items, with some equating to a £1 difference compared to a Tesco online shop. These figures demonstrate that islanders do not have access to the more competitively priced food which large mainland retailers provide. There were no clear differences in the price and quality of the items relating to the type of shop the community researchers visited because of two significant reasons. Firstly, the shops in Uist and Barra are generally classed as a small supermarket or local store; the largest retailer being the Co-operative supermarkets. There isn’t the same price advantage as seen on the mainland which a superstore or budget supermarket offers. Secondly, there is limited stock of own brand and value range goods throughout these stores so when set against the difficulties in the supply chains means all the shops are being simultaneously affected reducing their product lines to the top branded more expensive goods being left on the shelves. This results in huge fluctuations in price for these staple goods even within the same store. For example, orange juice was recorded by our researchers at its lowest price of £1.35 in the Co-op stores and at its highest of £4.15 for the same product; the former is a Co-op’s own brand of orange juice and the latter a top branded good which was the only option left on the shelves for our community researcher.

Figure 4 – Price ranges found for all items on the shopping list

Figure 5 – Price ranges found for all the items on the shopping list

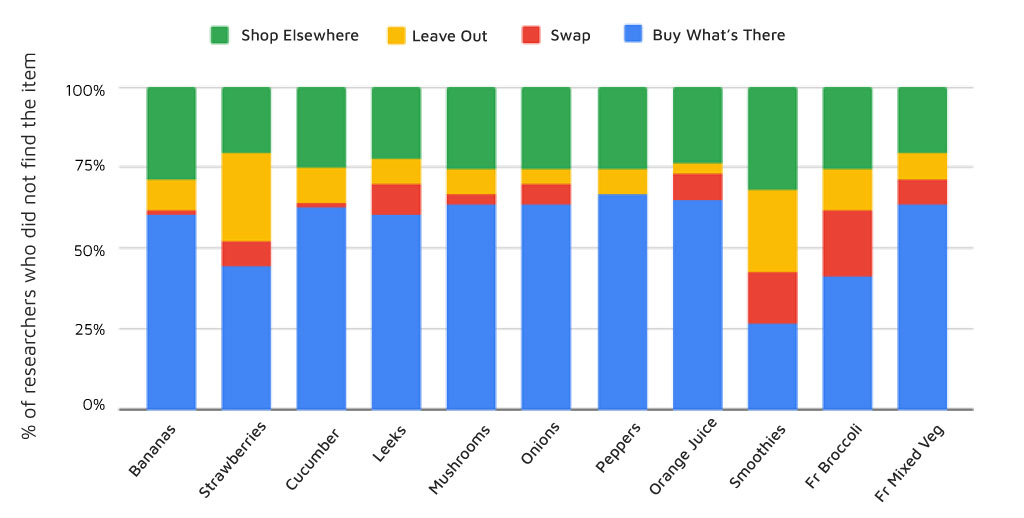

There is a dynamic relationship at play between the availability and affordability of essential fruit and vegetable items on the Robinsons Family shopping list within an island context. If an item was deemed unavailable, community researchers were asked to consider what the Robinsons would do (find an alternative, look in another shop or leave it out). As all the stores are being concurrently affected by continuous transport disruptions the only choice for the ‘Robinson family’ is to find an alternative or go without.

The cost implication for taking the ‘close alternative’ item was difficult to measure accurately across all 17 items as this may have been a different product entirely with varying weights and sizes. However, where we could analyse this, it gave us further insights revealing that the substitute product ended up being a top branded good which was packaged in smaller quantities than what was required and cost significantly more. For example, all the researchers throughout the islands found it difficult to find frozen vegetables as there was limited stock and choice even in the best of times. The task was to find 900g bag of frozen broccoli and 1kg bag of mixed vegetables so when these food items were not available the close alternative product on average cost 110% more for frozen broccoli and 150% more for frozen mixed vegetables. Rather than paying £1.10 for a 1kg bag of mixed vegetables (Tesco Online) islanders were on average paying £2.87 and sometimes forking out £4.67 for frozen mixed vegetables.

This same trend was found against other food items with pasta sauce equating to 233% more than a Tesco equivalent; paying £2.83 for a 500g jar of pasta sauce compared with £0.85 for a Tesco product. These ‘alternative’ prices have not been accounted for in these statistics across all food items but could dramatically increase the disparity further.

“There are not a lot of options in this shop. I don’t buy any biscuits or cakes anymore as they are so expensive. I bought a 400g bag of Tetley teabags last week and it cost me £7, I was literally in shock at the price. I would have bought a cheaper one, but there was no cheaper option, they were more expensive. There are more unhealthy options in the shop which are cheaper to buy, e.g., microwave burgers and pies.”

Figure 6 – Price ranges found for 14 items on the shopping list

Items that were more likely to be ‘left out’ than swapped included strawberries and individually packed smoothies. Researchers explained that for these items, it was at times difficult to find suitable alternatives and in general it was the soft fruits and vegetables that were most affected by cancelled ferries because they deteriorated sooner.

“Perishables like berries again have limited shelf life due to time from getting from Glasgow to Inverness then onto island.”

The Researchers found there were few options to swap or find a close alternative and ‘you just had to take what’s there’ even if the alternative was considerably more expensive, an inferior quality of product or about to perish. This conflicted with the evidence from Nourish Scotland’s research in 2022 with other local authority areas as most researchers on the mainland even in rural areas thought the Robinson’s family would look in another shop to find most items on the list. Highlighting that island communities are disproportionately more disadvantaged in terms of affording and gaining access to basic fruit and vegetable items.

Some researchers suggested swapping items for something else, while considering how this would affect the Robinson Family’s weekly meal plan. In some places, for instance, orange juice was only available from concentrate with a higher sugar content than the community advisors had specified. Researchers also highlighted the price benefit of opting for fresh vegetables sold loose rather than packaged recognising not only the cost savings in some cases but also the environmental benefits with the overall preference being to see fresh fruit and vegetables being displayed like a traditional greengrocer.

Figure 7 – Community Researchers’ decisions about items that were not found ‘easily’ or ‘fairly easily’

Our Community Researchers noticed reductions in packaging sizes; 5 apples in a pack rather than 6, and smaller tins for the same price which will impact on larger families. Packaging also prohibited our researchers from seeing the quality of the vegetables as the main concern for all our researchers was the goods freshness and the ability to check sell by dates and for items to be clearly price marked.

“Need to be very careful to check sell by dates when doing a week's shopping.”

“The use by dates are usually very short so it's hard to do a weekly shop as the fruit won't keep all week. Fruit is usually completely tasteless.”

Our researchers resoundingly agreed that home grown produce from the Islands is of high quality – it is the best! There was a sense of pride and recognition that all the ingredients to produce a high value premium product existed on the Islands although not often accessible and sometimes expensive.

Our community researchers noticed reductions in packaging sizes; five apples in a pack rather than six, and smaller tins for the same price which will impact on larger families. Packaging also prohibited our researchers from seeing the quality of the vegetables. The main concern for all our researchers was that the goods were fresh and clearly priced with sell by date labelling.

“Need to be very careful to check sell by dates when doing a week’s shopping.”

“The use by dates are usually very short so it’s hard to do a weekly shop as the fruit won’t keep all week. Fruit is usually completely tasteless.”

Our researchers resoundingly agreed that home grown produce from the islands is of high quality – it is the best! There was a sense of pride and recognition that all the ingredients to produce a high value premium product existed on the islands although not often accessible and sometimes expensive.

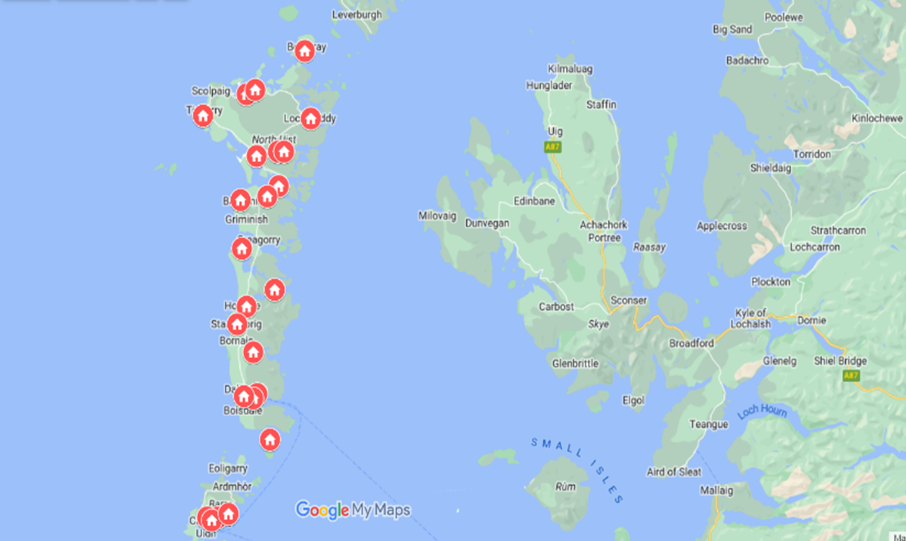

Uist’s linear geography, which extends 60 miles from Berneray to Eriskay, with a population of approximately 4,500 people, can make buying and delivering food difficult. The shops are located in the following areas Eriskay, Daliburgh, Carnan, Creagorry, Balivanich, Bayhead, Lochmaddy, Sollas, and Berneray with many households located many miles away from the nearest outlet. This in contrast to just two or three generations ago, preceding the islands being linked by causeways, there would be a merchant’s shop in every community. This is added to by the lack of value chain development support for the local market, as well as the need for increased food processing, finishing, storage and market facilities on Uist. Barra faces similar challenges within their food system as they are also reliant on a Calmac ferry, in this case from Oban, to transport produce onto the island and their population of 1,073 is dispersed throughout the Island with a township base at Castlebay where most of the surveyed shops were based.

Figure 8: Location of Community Researchers and Island Stores

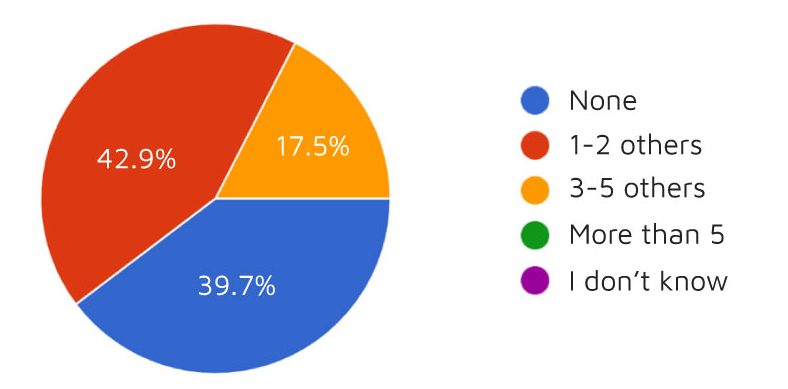

Not surprisingly, our survey revealed that approximately 40% of our community researchers did not live in a 10-mile radius of a shop with a further 43% of researchers stating that only 1-2 shops were in a 10-mile radius of their home. Thus, equating to a total of 80% of our researchers without easy reach of a local shop of any description and reliant on own transport to commute to the main supermarkets for their ‘big shop’ using the local township shops to ‘top up’ on items. Public transport is also limited across the islands and not operational after 6pm and there is no service on a Sunday.

Figure 9: Commuting distance to island stores

“People do their big shop here [Creagorry Co-op] as there is no other shop close to us. You really need a car to get to this shop, otherwise you have to take a taxi. You could get a bus to the shop, but you would be waiting a few hours for a bus back home, so it is not practical.”

“I tend to plan in a trip to a bigger shop with other activities/ jobs as fitting in the longer drive can sometime be very difficult.”

These findings connect back to the buying decisions of our researchers when items on the shopping list are unavailable because they believed the ‘Robinson family’ would not travel to another store or revisit the same store later in the day or week becomes it proves too costly on time and finance.

“Timing of going to shops used to be more predictable than now (re ferries) which makes getting all the shopping needed in one go more difficult. This trip was to partly to catch up with items not got the day before at the end of the weekend shop for the week – hence did not go to yet another shop at 5.30pm in the evening 25 mins away for items not on the shelf.”

“I’ve said they’d buy what was available but I don’t know. People have busy lives and if they can get everything in one shop that’s what they’ll do.”

“No smoothie and budget juice but better than nothing and does not justify driving elsewhere!”

However, it was noted by most of the community researchers that the local convenience shops although expensive at times operate as a good focal point within each of the townships; providing a good range of produce and is where the elderly and those without transport tend to shop.

“Most families here will do a weekly shop at the coop and then just grab something in passing at the butchers. Older people in the community are more likely to go to the butchers than the coop as they like shopping with people they know and having a blether. Also community notices are posted at the butchers so folk often stop by to check that. For me the butchers is a last resort shop when the coop is low on stock. The coop is horrifically expensive, but the butchers is even worse.”

“This is not a shop you would go to for the “big shop” but I do tend to do a lot of my shopping here due to convenience. It is next to my children’s school and is the shop I pass most frequently so although I don’t go in with the “big shop” in mind I do think we buy a large proportion of our weekly food here as it is much more convenient than travelling to one of the bigger shops. I tend to plan in a trip to a bigger shop with other activities/jobs as fitting in the longer drive can sometime be very difficult. This shop also has a filling station and is walking distance from a busy (For Uist) township.”

“Some single people and those without transport will do their weekly shop here as it has an extensive range of food including fresh meat, fresh fish and local bakery items. It is fairly expensive but quality good.”

Community researchers were asked to consider how differences in availability and prices would influence whether the Robinson Family would go on to purchase and eat each of the items. Over time, these decisions would affect the family’s ability to enjoy the balance of fruit and vegetables community advisors had agreed would meet the family’s needs.

“Shelves are often bare and I was surprised at how much I was able to find today. I find the shop stocks up mostly on unhealthy stuff. We often joke that the Co-op is never short of alcohol or chocolate! I really struggle to eat healthily as I can’t plan meals. I never know what will be available. I work long hours. I want to have frozen vegetables that’s prepped and ready to go so I can make quick, healthy meals, but I find it so hard with limited selection, and this is the best shop on the island! There’s just me and my husband and we make do as best we can, but it must be incredibly difficult for families with young children.”

“There have been ferry disruptions which have an impact on stock in the shops. You can go shopping with a shopping list, but often can’t find what you need and have to think of new dinner ideas instead.”

In summary, islanders living in the 8 Outer Hebridean Islands from Berneray to Barra are disproportionately disadvantaged in terms of affording and gaining access to basic fruit and vegetable items, through their island stores, compared to any mainland rural area. Uist and Barra residents are not gaining the nutritional benefits of fresh produce, particularly during the autumn and winter months, due to the reliance of long food supply chains and with transport disruptions this further impacts on the quality and freshness of these items. Compounding these dietary inequalities is the fact these island communities are also significantly disadvantaged by the price of these goods and shoulder the burden of an ‘island premium’ which far exceeds a ‘rural premium’ on food items.

There is now a strong call by our community researchers for immediate and progressive action by national and regional authorities to address these difficulties in a meaningful way. Action which promotes a truly dignified island food system; one where everyone is food secure, with access to adequate, nutritious, and culturally appropriate food, without the need of emergency food aid. It is one where the right to food is understood as a matter of justice rather than charity and allows for a Good Food Nation in which every community’s health and well-being is paramount and no-one is left behind. Our island communities demand nothing less because a right to food is a right for all.

Ensuring that families can afford a variety of good quality produce is an important way to support people to buy and eat more fruit and vegetables. This could include actions that improve the availability of a wider variety of fruits and vegetables in smaller supermarkets, corner shops and convenience stores so that people do not need to travel to the mainland or order online. A community wealth building and well-being strategy which also includes actions that support smaller retailers to offer a more affordable selection of fruit and vegetables, especially ones that children and families enjoy but may leave out if too expensive locally.

Our community researchers want to see more own brand and value range produce in their supermarkets and for the Co-operative stores to be classed as supermarkets as opposed to convenience stores which would give priority to healthier food products and not convenience food. Particularly when the Co-op stores is the predominant food retailer serving these islands. Researchers and store managers recognise the need for more agile ordering systems which are overseen by store analysts who have sight of the Calmac ferry cancellations and can even out the peaks and troughs in the ordering system beyond the peak seasons and to individual food items. This would help minimise on food wastage whilst ensuring a regular flow of produce is being transported to Uist and Barra.

Community researchers believe that there is great potential to increase the amount of local food available to the local community and provide horticultural training to encourage people to grow locally. This could be a key response, along with a refillery service for Uist, to improving access to affordable nutritious food. This would help build the community well-being of those living in Uist and Barra and create a more resilient food system which everyone benefits.

Wider actions, such as improving affordable transport links for people without cars or making delivery options more accessible to everyone, would also help to overcome some of the barriers identified by community researchers. The Scottish Government could support these islands through an island uplift payment particularly catering to the most vulnerable people in the community - the elderly and children. Further support to improve local availability and affordability of essential fruit and vegetables items could help widen access as well as sustaining these important components of local communities.

All four pillars of food security (availability, access, utilisation, and stability) have been impacted negatively in Uist and Barra in recent years. The precarious nature of our access to sufficient nutritious food is stark and demands that we look at solutions closer to home which is supported at all levels of government.

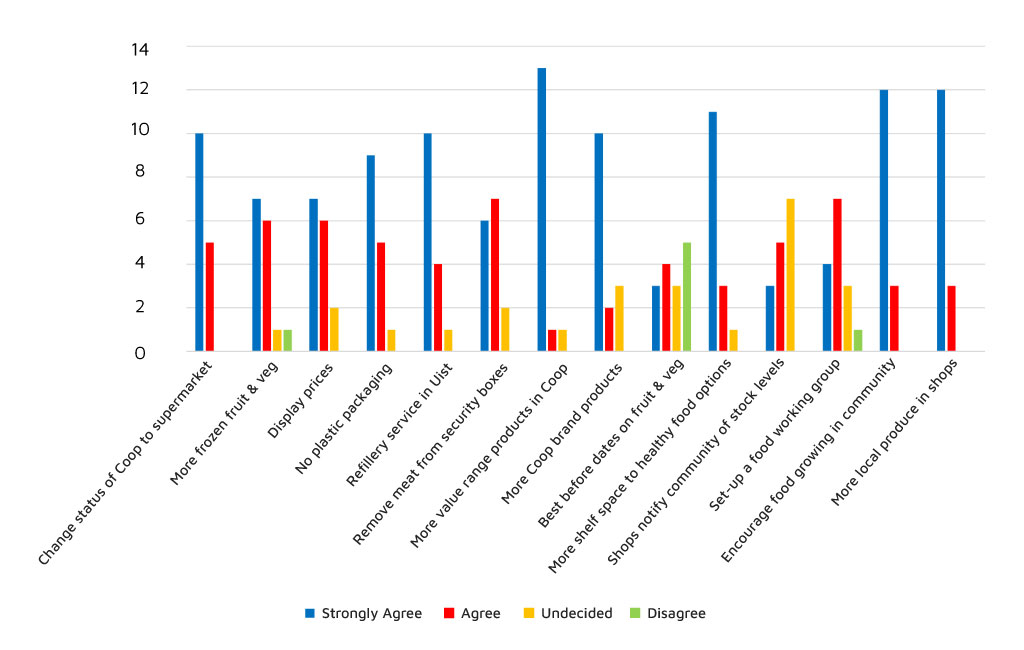

Figure 10: Community researcher’s recommendations and next steps.

GET IN TOUCH

Send us a message!